Apollo 13

Odyssey's damaged service module, as seen from the Apollo Lunar Module Aquarius, hours before reentry | |

| Mission type | Crewed lunar landing attempt (H) |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID |

|

| SATCAT no. | 4371[1] |

| Mission duration | 5 days, 22 hours, 54 minutes, 41 seconds[2] |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft |

|

| Manufacturer |

|

| Launch mass | 44,069 kg (CSM: 28,881 kg;[3] LM: 15,188 kg)[4] |

| Landing mass | 5,050 kilograms (11,133 lb)[5] |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 3 |

| Members | |

| Callsign |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | April 11, 1970, 19:13:00 UTC[6] |

| Rocket | Saturn V SA-508 |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | USS Iwo Jima |

| Landing date | April 17, 1970, 18:07:41 UTC |

| Landing site | South Pacific Ocean 21°38′24″S 165°21′42″W / 21.64000°S 165.36167°W |

| Flyby of Moon (orbit and landing aborted) | |

| Closest approach | April 15, 1970, 00:21:00 UTC |

| Distance | 254 kilometers (137 nmi) |

| Docking with LM | |

| Docking date | April 11, 1970, 22:32:08 UTC |

| Undocking date | April 17, 1970, 16:43:00 UTC |

Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, Fred Haise | |

Apollo 13 (April 11–17, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and would have been the third Moon landing. The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the landing was aborted after an oxygen tank in the service module (SM) exploded two days into the mission, disabling its electrical and life-support system. The crew, supported by backup systems on the lunar module (LM), instead looped around the Moon in a circumlunar trajectory and returned safely to Earth on April 17. The mission was commanded by Jim Lovell, with Jack Swigert as command module (CM) pilot and Fred Haise as lunar module (LM) pilot. Swigert was a late replacement for Ken Mattingly, who was grounded after exposure to rubella.

A routine stir of an oxygen tank ignited damaged wire insulation inside it, causing an explosion that vented the contents of both of the SM's oxygen tanks to space.[note 1] Without oxygen, needed for breathing and for generating electric power, the SM's propulsion and life support systems could not operate. The CM's systems had to be shut down to conserve its remaining resources for reentry, forcing the crew to transfer to the LM as a lifeboat. With the lunar landing canceled, mission controllers worked to bring the crew home alive.

Although the LM was designed to support two men on the lunar surface for two days, Mission Control in Houston improvised new procedures so it could support three men for four days. The crew experienced great hardship, caused by limited power, a chilly and wet cabin and a shortage of potable water. There was a critical need to adapt the CM's cartridges for the carbon dioxide scrubber system to work in the LM; the crew and mission controllers were successful in improvising a solution. The astronauts' peril briefly renewed public interest in the Apollo program; tens of millions watched the splashdown in the South Pacific Ocean on television.

An investigative review board found fault with preflight testing of the oxygen tank and Teflon being placed inside it. The board recommended changes, including minimizing the use of potentially combustible items inside the tank; this was done for Apollo 14. The story of Apollo 13 has been dramatized several times, most notably in the 1995 film Apollo 13 based on Lost Moon, the 1994 memoir co-authored by Lovell – and an episode of the 1998 miniseries From the Earth to the Moon.

Background

In 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy challenged his nation to land an astronaut on the Moon by the end of the decade, with a safe return to Earth.[11] NASA worked towards this goal incrementally, sending astronauts into space during Project Mercury and Project Gemini, leading up to the Apollo program.[12] The goal was achieved with Apollo 11, which landed on the Moon on July 20, 1969. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the lunar surface while Michael Collins orbited the Moon in Command Module Columbia. The mission returned to Earth on July 24, 1969, fulfilling Kennedy's challenge.[11]

NASA had contracted for fifteen Saturn V rockets to achieve the goal; at the time no one knew how many missions this would require.[13] Since success was obtained in 1969 with the sixth Saturn V on Apollo 11, nine rockets remained available for a hoped-for total of ten landings. After the excitement of Apollo 11, the general public grew apathetic towards the space program and Congress continued to cut NASA's budget; Apollo 20 was canceled.[14] Despite the successful lunar landing, the missions were considered so risky that astronauts could not afford life insurance to provide for their families if they died in space.[note 2][15]

Even before the first U.S. astronaut entered space in 1961, planning for a centralized facility to communicate with the spacecraft and monitor its performance had begun, for the most part the brainchild of Christopher C. Kraft Jr., who became NASA's first flight director. During John Glenn's Mercury Friendship 7 flight in February 1962 (the first crewed orbital flight by the U.S.), one of Kraft's decisions was overruled by NASA managers. He was vindicated by post-mission analysis and implemented a rule that, during the mission, the flight director's word was absolute[16] – to overrule him, NASA would have to fire him on the spot.[17] Flight directors during Apollo had a one-sentence job description, "The flight director may take any actions necessary for crew safety and mission success."[18]

Houston's Mission Control Center was opened in 1965. It was in part designed by Kraft and now named for him.[16] In Mission Control, each flight controller, in addition to monitoring telemetry from the spacecraft, was in communication via voice loop to specialists in a Staff Support Room (or "back room"), who focused on specific spacecraft systems.[17]

Apollo 13 was to be the second H mission, meant to demonstrate precision lunar landings and explore specific sites on the Moon.[19] With Kennedy's goal accomplished by Apollo 11, and Apollo 12 demonstrating that the astronauts could perform a precision landing, mission planners were able to focus on more than just landing safely and having astronauts minimally trained in geology gather lunar samples to take home to Earth. There was a greater role for science on Apollo 13, especially for geology, something emphasized by the mission's motto, Ex luna, scientia (From the Moon, knowledge).[20]

Astronauts and key Mission Control personnel

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander (CDR) | James A. Lovell Jr. Fourth and last spaceflight | |

| Command Module Pilot (CMP) | John "Jack" L. Swigert Jr. Only spaceflight | |

| Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) | Fred W. Haise Jr. Only spaceflight | |

Apollo 13's mission commander, Jim Lovell, was 42 years old at the time of the spaceflight. He was a graduate of the United States Naval Academy and had been a naval aviator and test pilot before being selected for the second group of astronauts in 1962; he flew with Frank Borman in Gemini 7 in 1965 and Buzz Aldrin in Gemini 12 the following year before flying in Apollo 8 in 1968, the first spacecraft to orbit the Moon.[21] At the time of Apollo 13, Lovell was the NASA astronaut with the most time in space, with 572 hours over the three missions.[22]

Jack Swigert, the command module pilot (CMP), was 38 years old and held a B.S. in mechanical engineering and an M.S. in aerospace science; he had served in the Air Force and in state Air National Guards and was an engineering test pilot before being selected for the fifth group of astronauts in 1966.[23] Fred Haise, the lunar module pilot (LMP), was 35 years old. He held a B.S. in aeronautical engineering, had been a Marine Corps fighter pilot, and was a civilian research pilot for NASA when he was selected as a Group 5 astronaut.[24][25]

According to the standard Apollo crew rotation, the prime crew for Apollo 13 would have been the backup crew[note 3] for Apollo 10, with Mercury and Gemini veteran Gordon Cooper in command, Donn F. Eisele as CMP and Edgar Mitchell as LMP. Deke Slayton, NASA's Director of Flight Crew Operations, never intended to rotate Cooper and Eisele to a prime crew assignment, as both were out of favor – Cooper for his lax attitude towards training, and Eisele for incidents aboard Apollo 7 and an extramarital affair. He assigned them to the backup crew because no other veteran astronauts were available.[28] Slayton's original choices for Apollo 13 were Alan Shepard as commander, Stuart Roosa as CMP, and Mitchell as LMP. However, management felt Shepard needed more training time, as he had only recently resumed active status after surgery for an inner ear disorder and had not flown since 1961. Thus, Lovell's crew (himself, Haise and Ken Mattingly), having all backed up Apollo 11 and being slated for Apollo 14, was swapped with Shepard's.[28]

Swigert was originally CMP of Apollo 13's backup crew, with John Young as commander and Charles Duke as lunar module pilot.[29] Seven days before launch, Duke contracted rubella from his son's friend.[30] This exposed both the prime and backup crews, who trained together. Of the five, only Mattingly was not immune through prior exposure. Normally, if any member of the prime crew had to be grounded, the remaining crew would be replaced as well, and the backup crew substituted, but Duke's illness ruled this out,[31] so two days before launch, Mattingly was replaced by Swigert.[23] Mattingly never developed rubella and later flew on Apollo 16.[32]

For Apollo, a third crew of astronauts, known as the support crew, was designated in addition to the prime and backup crews used on projects Mercury and Gemini. Slayton created the support crews because James McDivitt, who would command Apollo 9, believed that, with preparation going on in facilities across the US, meetings that needed a member of the flight crew would be missed. Support crew members were to assist as directed by the mission commander.[33] Usually low in seniority, they assembled the mission's rules, flight plan, and checklists, and kept them updated;[34][35] for Apollo 13, they were Vance D. Brand, Jack Lousma and either William Pogue or Joseph Kerwin.[note 4][40]

For Apollo 13, flight directors were Gene Kranz, White team[41] (the lead flight director);[42][43] Glynn Lunney, Black team; Milton Windler, Maroon team and Gerry Griffin, Gold team.[41] The CAPCOMs (the person in Mission Control, during the Apollo program an astronaut, who was responsible for voice communications with the crew)[44] for Apollo 13 were Kerwin, Brand, Lousma, Young and Mattingly.[45]

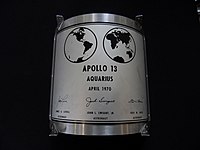

Mission insignia and call signs

The Apollo 13 mission insignia depicts the Greek god of the Sun, Apollo, with three horses pulling his chariot across the face of the Moon, and the Earth seen in the distance. This is meant to symbolize the Apollo flights bringing the light of knowledge to all people. The mission motto, Ex luna, scientia ("From the Moon, knowledge"), appears. In choosing it, Lovell adapted the motto of his alma mater, the Naval Academy, Ex scientia, tridens ("From knowledge, sea power").[46][47]

On the patch, the mission number appeared in Roman numerals as Apollo XIII. It did not have to be modified after Swigert replaced Mattingly, as it is one of only two Apollo mission insignia – the other being Apollo 11 – not to include the names of the crew. It was designed by artist Lumen Martin Winter, who based it on a mural he had painted for the St. Regis Hotel in New York City.[48] The mural was later purchased by actor Tom Hanks,[49] who portrayed Lovell in the movie Apollo 13, and it is now in the Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center in Illinois.[50]

The mission's motto was in Lovell's mind when he chose the call sign Aquarius for the lunar module, taken from Aquarius, the bringer of water.[51][52] Some in the media erroneously reported that the call sign was taken from a song by that name from the musical Hair.[52][53] The command module's call sign, Odyssey, was chosen not only for its Homeric association but to refer to the recent film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, based on a short story by science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke.[51] In his book, Lovell indicated he chose the name Odyssey because he liked the word and its definition: a long voyage with many changes of fortune.[52]

Due to the accident and the last minute crew change of Jack Swigert replacing Ken Mattingly three days prior to launch, the Apollo 13 Robbins medallions flown aboard the mission were melted down and reminted after the mission to reflect the correct crew, and the absence of a lunar landing date.[54]

Space vehicle

The Saturn V rocket used to carry Apollo 13 to the Moon was numbered SA-508, and was almost identical to those used on Apollo 8 through 12.[55] Including the spacecraft, the rocket weighed in at 2,949,136 kilograms (6,501,733 lb).[56] The S-IC first stage's engines were rated to generate 440,000 newtons (100,000 lbf) less total thrust than Apollo 12's, though they remained within specifications.[57] To keep its liquid hydrogen propellent cold, the S-II second stage's cryogenic tanks were insulated; on earlier Apollo missions this came in the form of panels that were affixed, but beginning with Apollo 13, insulation was sprayed onto the exterior of the tanks.[58] Extra propellant was carried as a test, since future J missions to the Moon would require more propellant for their heavier payloads. This made the vehicle the heaviest yet flown by NASA, and Apollo 13 was visibly slower to clear the launch tower than earlier missions.[57]

The Apollo 13 spacecraft consisted of Command Module 109 and Service Module 109 (together CSM-109), called Odyssey, and Lunar Module 7 (LM-7), called Aquarius. Also considered part of the spacecraft was the launch escape system, which would propel the command module (CM) to safety in the event of a problem during liftoff, and the Spacecraft–LM Adapter, numbered as SLA-16, which housed the lunar module (LM) during the first hours of the mission.[59][60]

The LM stages, CM and service module (SM) were received at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in June 1969; the portions of the Saturn V were received in June and July. Thereafter, testing and assembly proceeded, culminating with the rollout of the launch vehicle, with the spacecraft atop it, on December 15, 1969.[59] Apollo 13 was originally scheduled for launch on March 12, 1970, but that January NASA announced the mission would be postponed until April 11, both to allow more time for planning and to spread the Apollo missions over a longer period.[61] The plan was to have two Apollo flights per year and was in response to budgetary constraints[62] that had recently seen the cancellation of Apollo 20.[63]

Training and preparation

The Apollo 13 prime crew undertook over 1,000 hours of mission-specific training, more than five hours for every hour of the mission's ten-day planned duration. Each member of the prime crew spent over 400 hours in simulators of the CM and (for Lovell and Haise) of the LM at KSC and at Houston, some of which involved the flight controllers at Mission Control.[64] Flight controllers participated in many simulations of problems with the spacecraft in flight, which taught them how to react in an emergency.[17] Specialized simulators at other locations were also used by the crew members.[64]

The astronauts of Apollo 11 had minimal time for geology training, with only six months between crew assignment and launch; higher priorities took much of their time.[65] Apollo 12 saw more such training, including practice in the field, using a CAPCOM and a simulated backroom of scientists, to whom the astronauts had to describe what they saw.[66] Scientist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt saw that there was limited enthusiasm for geology field trips. Believing an inspirational teacher was needed, Schmitt arranged for Lovell and Haise to meet his old professor, Caltech's Lee Silver. The two astronauts, and backups Young and Duke, went on a field trip with Silver at their own time and expense. At the end of their week together, Lovell made Silver their geology mentor, who would be extensively involved in the geology planning for Apollo 13.[67] Farouk El-Baz oversaw the training of Mattingly and his backup, Swigert, which involved describing and photographing simulated lunar landmarks from airplanes.[68] El-Baz had all three prime crew astronauts describe geologic features they saw during their flights between Houston and KSC; Mattingly's enthusiasm caused other astronauts, such as Apollo 14's CMP, Roosa, to seek out El-Baz as a teacher.[69]

Concerned about how close Apollo 11's LM, Eagle, had come to running out of propellant during its lunar descent, mission planners decided that beginning with Apollo 13, the CSM would bring the LM to the low orbit from which the landing attempt would commence. This was a change from Apollo 11 and 12, on which the LM made the burn to bring it to the lower orbit. The change was part of an effort to increase the amount of hover time available to the astronauts as the missions headed into rougher terrain.[70]

The plan was to devote the first of the two four-hour lunar surface extravehicular activities (EVAs) to setting up the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) group of scientific instruments; during the second, Lovell and Haise would investigate Cone crater, near the planned landing site.[71] The two astronauts wore their spacesuits for some 20 walk-throughs of EVA procedures, including sample gathering and use of tools and other equipment. They flew in the "Vomit Comet" in simulated microgravity or lunar gravity, including practice in donning and doffing spacesuits. To prepare for the descent to the Moon's surface, Lovell flew the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV) after receiving helicopter training.[72] Despite the crashes of one LLTV and one similar Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) prior to Apollo 13, mission commanders considered flying them invaluable experience and so prevailed on reluctant NASA management to retain them.[73]

Experiments and scientific objectives

Apollo 13's designated landing site was near Fra Mauro crater; the Fra Mauro formation was believed to contain much material spattered by the impact that had filled the Imbrium basin early in the Moon's history. Dating it would provide information not only about the Moon, but about the Earth's early history. Such material was likely to be available at Cone crater, a site where an impact was believed to have drilled deep into the lunar regolith.[74]

Apollo 11 had left a seismometer on the Moon, but the solar-powered unit did not survive its first two-week-long lunar night. The Apollo 12 astronauts also left one as part of its ALSEP, which was nuclear-powered.[75] Apollo 13 also carried a seismometer (known as the Passive Seismic Experiment, or PSE), similar to Apollo 12's, as part of its ALSEP, to be left on the Moon by the astronauts.[76] That seismometer was to be calibrated by the impact, after jettison, of the ascent stage of Apollo 13's LM, an object of known mass and velocity impacting at a known location.[77]

Other ALSEP experiments on Apollo 13 included a Heat Flow Experiment (HFE), which would involve drilling two holes 3.0 metres (10 ft) deep.[78] This was Haise's responsibility; he was also to drill a third hole of that depth for a core sample.[79] A Charged Particle Lunar Environment Experiment (CPLEE) measured the protons and electrons of solar origin reaching the Moon.[80] The package also included a Lunar Atmosphere Detector (LAD)[81] and a Dust Detector, to measure the accumulation of debris.[82] The Heat Flow Experiment and the CPLEE were flown for the first time on Apollo 13; the other experiments had been flown before.[79]

To power the ALSEP, the SNAP-27 radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) was flown. Developed by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, SNAP-27 was first flown on Apollo 12. The fuel capsule contained about 3.79 kilograms (8.36 lb) of plutonium oxide. The cask placed around the capsule for transport to the Moon was built with heat shields of graphite and of beryllium, and with structural parts of titanium and of Inconel materials. Thus, it was built to withstand the heat of reentry into the Earth's atmosphere rather than pollute the air with plutonium in the event of an aborted mission.[83]

A United States flag was also taken, to be erected on the Moon's surface.[84] For Apollo 11 and 12, the flag had been placed in a heat-resistant tube on the front landing leg; it was moved for Apollo 13 to the Modularized Equipment Stowage Assembly (MESA) in the LM descent stage. The structure to fly the flag on the airless Moon was improved from Apollo 12's.[85]

For the first time, red stripes were placed on the helmet, arms and legs of the commander's A7L spacesuit. This was done as, after Apollo 11, those reviewing the images taken had trouble distinguishing Armstrong from Aldrin, but the change was approved too late for Apollo 12.[86] New drink bags that attached inside the helmets and were to be sipped from as the astronauts walked on the Moon were demonstrated by Haise during Apollo 13's final television broadcast before the accident.[87][88]

Apollo 13's primary mission objectives were to: "Perform selenological inspection, survey, and sampling of materials in a preselected region of the Fra Mauro Formation. Deploy and activate an Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package. Develop man's capability to work in the lunar environment. Obtain photographs of candidate exploration sites."[89] The astronauts were also to accomplish other photographic objectives, including of the Gegenschein from lunar orbit, and of the Moon itself on the journey back to Earth. Some of this photography was to be performed by Swigert as Lovell and Haise walked on the Moon.[90] Swigert was also to take photographs of the Lagrangian points of the Earth-Moon system. Apollo 13 had twelve cameras on board, including those for television and moving pictures.[79] The crew was also to downlink bistatic radar observations of the Moon. None of these was attempted because of the accident.[90]

Flight of Apollo 13

Launch and translunar injection

The mission was launched at the planned time, 2:13:00 pm EST (19:13:00 UTC) on April 11. An anomaly occurred when the second-stage, center (inboard) engine shut down about two minutes early.[91][92] This was caused by severe pogo oscillations. Starting with Apollo 10, the vehicle's guidance system was designed to shut the engine down in response to chamber pressure excursions.[93] Pogo oscillations had occurred on Titan rockets (used during the Gemini program) and on previous Apollo missions,[94][95] but on Apollo 13 they were amplified by an interaction with turbopump cavitation.[96][97] A fix to prevent pogo was ready for the mission, but schedule pressure did not permit the hardware's integration into the Apollo 13 vehicle.[93][98] A post-flight investigation revealed the engine was one cycle away from catastrophic failure.[93] The four outboard engines and the S-IVB third stage burned longer to compensate, and the vehicle achieved very close to the planned circular 190 kilometers (120 mi; 100 nmi) parking orbit, followed by a translunar injection (TLI) about two hours later, setting the mission on course for the Moon.[91][92]

After TLI, Swigert performed the separation and transposition maneuvers before docking the CSM Odyssey to the LM Aquarius, and the spacecraft pulled away from the third stage.[99] Ground controllers then sent the third stage on a course to impact the Moon in range of the Apollo 12 seismometer, which it did just over three days into the mission.[100]

The crew settled in for the three-day trip to Fra Mauro. At 30:40:50 into the mission, with the TV camera running, the crew performed a burn to place Apollo 13 on a hybrid trajectory. The departure from a free-return trajectory meant that if no further burns were performed, Apollo 13 would miss Earth on its return trajectory, rather than intercept it, as with a free return.[101] A free return trajectory could only reach sites near the lunar equator; a hybrid trajectory, which could be started at any point after TLI, allowed sites with higher latitudes, such as Fra Mauro, to be reached.[102] Communications were enlivened when Swigert realized that in the last-minute rush, he had omitted to file his federal income tax return (due April 15), and amid laughter from mission controllers, asked how he could get an extension. He was found to be entitled to a 60-day extension for being out of the country at the deadline.[103]

Entry into the LM to test its systems had been scheduled for 58:00:00; when the crew awoke on the third day of the mission, they were informed it had been moved up three hours and was later moved up again by another hour. A television broadcast was scheduled for 55:00:00; Lovell, acting as emcee, showed the audience the interiors of Odyssey and Aquarius.[104] The audience was limited since none of the television networks were carrying the broadcast,[105] forcing Marilyn Lovell (Jim Lovell's wife) to go to the VIP room at Mission Control if she wanted to watch her husband and his crewmates.[106]

Accident

About six and a half minutes after the TV broadcast – approaching 56:00:00 – Apollo 13 was about 180,000 nautical miles (210,000 mi; 330,000 km) from Earth.[107] Haise was completing the shutdown of the LM after testing its systems while Lovell stowed the TV camera. Jack Lousma, the CAPCOM, sent minor instructions to Swigert, including changing the attitude of the craft to facilitate photography of Comet Bennett.[107][108]

The pressure sensor in one of the SM's oxygen tanks had earlier appeared to be malfunctioning, so Sy Liebergot (the EECOM, in charge of monitoring the CSM's electrical system) requested that the stirring fans in the tanks be activated. Normally this was done once daily; a stir would destratify the contents of the tanks, making the pressure readings more accurate.[107] The Flight Director, Kranz, had Liebergot wait a few minutes for the crew to settle down after the telecast,[109] then Lousma relayed the request to Swigert, who activated the switches controlling the fans,[107] and after a few seconds turned them off again.[108]

Ninety-five seconds after Swigert activated those switches,[109] the astronauts heard a "pretty large bang", accompanied by fluctuations in electrical power and the firing of the attitude control thrusters.[110][111] Communications and telemetry to Earth were lost for 1.8 seconds, until the system automatically corrected by switching the high-gain S-band antenna, used for translunar communications, from narrow-beam to wide-beam mode.[112] The accident happened at 55:54:53 (03:08 UTC on April 14, 10:08 PM EST, April 13). Swigert reported 26 seconds later, "Okay, Houston, we've had a problem here," echoed at 55:55:42 by Lovell, "Houston, we've had a problem. We've had a Main B Bus undervolt."[107] William Fenner was the guidance officer (GUIDO) who was the first to report a problem in the control room to Kranz.[107]

Lovell's initial thought on hearing the noise was that Haise had activated the LM's cabin-repressurization valve, which also produced a bang (Haise enjoyed doing so to startle his crewmates), but Lovell could see that Haise had no idea what had happened. Swigert initially thought that a meteoroid might have struck the LM, but he and Lovell quickly realized there was no leak.[113] The "Main Bus B undervolt" meant that there was insufficient voltage produced by the SM's three fuel cells (fueled by hydrogen and oxygen piped from their respective tanks) to the second of the SM's two electric power distribution systems. Almost everything in the CSM required power. Although the bus momentarily returned to normal status, soon both buses A and B were short on voltage. Haise checked the status of the fuel cells and found that two of them were dead. Mission rules forbade entering lunar orbit unless all fuel cells were operational.[114]

In the minutes after the accident, there were several unusual readings, showing that tank 2 was empty and tank 1's pressure slowly falling, that the computer on the spacecraft had reset and that the high-gain antenna was not working. Liebergot initially missed the worrying signs from tank 2 following the stir, as he was focusing on tank 1, believing that its reading would be a good guide to what was present in tank 2, as did controllers supporting him in the "back room". When Kranz questioned Liebergot on this, he initially responded that there might be false readings due to an instrumentation problem; he was often teased about that in the years to come.[17] Lovell, looking out the window, reported "a gas of some sort" venting into space, making it clear that there was a serious problem.[115]

Since the fuel cells needed oxygen to operate, when Oxygen Tank 1 ran dry, the remaining fuel cell would shut down, meaning the CSM's only significant sources of power and oxygen would be the CM's batteries and its oxygen "surge tank". These would be needed for the final hours of the mission, but the remaining fuel cell, already starved for oxygen, was drawing from the surge tank. Kranz ordered the surge tank isolated, saving its oxygen, but this meant that the remaining fuel cell would die within two hours, as the oxygen in tank 1 was consumed or leaked away.[114] The volume surrounding the spacecraft was filled with myriad small bits of debris from the accident, complicating any efforts to use the stars for navigation.[116] The mission's goal became simply getting the astronauts back to Earth alive.[117]

Looping around the Moon

The lunar module had charged batteries and full oxygen tanks for use on the lunar surface, so Kranz directed that the astronauts power up the LM and use it as a "lifeboat"[17] – a scenario anticipated but considered unlikely.[118] Procedures for using the LM in this way had been developed by LM flight controllers after a training simulation for Apollo 10 in which the LM was needed for survival, but could not be powered up in time.[117] Had Apollo 13's accident occurred on the return voyage, with the LM already jettisoned, the astronauts would have died,[119] as they would have following an explosion in lunar orbit, including one while Lovell and Haise walked on the Moon.[120]

A key decision was the choice of return path. A "direct abort" would use the SM's main engine (the Service Propulsion System or SPS) to return before reaching the Moon. However, the accident could have damaged the SPS, and the fuel cells would have to last at least another hour to meet its power requirements, so Kranz instead decided on a longer route: the spacecraft would swing around the Moon before heading back to Earth. Apollo 13 was on the hybrid trajectory which was to take it to Fra Mauro; it now needed to be brought back to a free return. The LM's Descent Propulsion System (DPS), although not as powerful as the SPS, could do this, but new software for Mission Control's computers needed to be written by technicians as it had never been contemplated that the CSM/LM spacecraft would have to be maneuvered from the LM. As the CM was being shut down, Lovell copied down its guidance system's orientation information and performed hand calculations to transfer it to the LM's guidance system, which had been turned off; at his request Mission Control checked his figures.[117][121] At 61:29:43.49 the DPS burn of 34.23 seconds took Apollo 13 back to a free return trajectory.[122]

The change would get Apollo 13 back to Earth in about four days' time – though with splashdown in the Indian Ocean, where NASA had few recovery forces. Jerry Bostick and other Flight Dynamics Officers (FIDOs) were anxious both to shorten the travel time and to move splashdown to the Pacific Ocean, where the main recovery forces were located. One option would shave 36 hours off the return time, but required jettisoning the SM; this would expose the CM's heat shield to space during the return journey, something for which it had not been designed. The FIDOs also proposed other solutions. After a meeting involving NASA officials and engineers, the senior individual present, Manned Spaceflight Center director Robert R. Gilruth, decided on a burn using the DPS, that would save 12 hours and land Apollo 13 in the Pacific. This "PC+2" burn would take place two hours after pericynthion, the closest approach to the Moon.[117] At pericynthion, Apollo 13 set the record (per the Guinness Book of World Records), which still stands, for the furthest distance from Earth by a crewed spacecraft: 400,171 kilometers (248,655 mi; 216,075 nmi) from Earth at 7:21 pm EST, April 14 (00:21:00 UTC April 15).[123][note 5]

While preparing for the burn, the crew was told that the S-IVB had impacted the Moon as planned, leading Lovell to quip, "Well, at least something worked on this flight."[126][127] Kranz's White team of mission controllers, who had spent most of their time supporting other teams and developing the procedures urgently needed to get the astronauts home, took their consoles for the PC+2 procedure.[128] Normally, the accuracy of such a burn could be assured by checking the alignment Lovell had transferred to the LM's computer against the position of one of the stars astronauts used for navigation, but the light glinting off the many pieces of debris accompanying the spacecraft made that impractical. The astronauts accordingly used the one star available whose position could not be obscured – the Sun. Houston also informed them that the Moon would be centered in the commander's window of the LM as they made the burn, which was almost perfect – less than 0.3 meters (1 foot) per second off.[126] The burn, at 79:27:38.95, lasted four minutes and 23 seconds.[129] The crew then shut down most LM systems to conserve consumables.[126]

Return to Earth

The LM carried enough oxygen, but that still left the problem of removing carbon dioxide, which was absorbed by canisters of lithium hydroxide pellets. The LM's stock of canisters, meant to accommodate two astronauts for 45 hours on the Moon, was not enough to support three astronauts for the return journey to Earth.[130] The CM had enough canisters, but they were of a different shape and size to the LM's, hence unable to be used in the LM's equipment. Engineers on the ground devised a way to bridge the gap, using plastic covers ripped from procedure manuals, duct tape, and other items available on the spacecraft.[131][132] NASA engineers referred to the improvised device as "the mailbox".[133] The procedure for building the device was read to the crew by CAPCOM Joseph Kerwin over the course of an hour, and was built by Swigert and Haise; carbon dioxide levels began dropping immediately. Lovell later described this improvisation as "a fine example of cooperation between ground and space".[134]

The CSM's electricity came from fuel cells that produced water as a byproduct, but the LM was powered by silver-zinc batteries which did not, so both electrical power and water (needed for equipment cooling as well as drinking) would be critical. LM power consumption was reduced to the lowest level possible;[135] Swigert was able to fill some drinking bags with water from the CM's water tap,[126] but even assuming rationing of personal consumption, Haise initially calculated they would run out of water for cooling about five hours before reentry. This seemed acceptable because the systems of Apollo 11's LM, once jettisoned in lunar orbit, had continued to operate for seven to eight hours even with the water cut off. In the end, Apollo 13 returned to Earth with 12.8 kilograms (28.2 lb) of water remaining.[136] The crew's ration was 0.2 liters (6.8 fl oz) of water per person per day; the three astronauts lost a total of 14 kilograms (31 lb) among them, and Haise developed a urinary tract infection.[137][138] This infection was probably caused by the reduced water intake, but microgravity and effects of cosmic radiation might have impaired his immune system's reaction to the pathogen.[139]

Inside the darkened spacecraft, the temperature dropped as low as 3 °C (38 °F).[140] Lovell considered having the crew don their spacesuits, but decided this would be too hot. Instead, Lovell and Haise wore their lunar EVA boots and Swigert put on an extra coverall. All three astronauts were cold, especially Swigert, who had got his feet wet while filling the water bags and had no lunar overshoes (since he had not been scheduled to walk on the Moon). As they had been told not to discharge their urine to space to avoid disturbing the trajectory, they had to store it in bags. Water condensed on the walls, though any condensation that may have been behind equipment panels[141] caused no problems, partly because of the extensive electrical insulation improvements instituted after the Apollo 1 fire.[142] Despite all this, the crew voiced few complaints.[143]

Flight controller John Aaron, along with Mattingly and several engineers and designers, devised a procedure for powering up the command module from full shutdown – something never intended to be done in flight, much less under Apollo 13's severe power and time constraints.[144] The astronauts implemented the procedure without apparent difficulty: Kranz later credited all three astronauts having been test pilots, accustomed to having to work in critical situations with their lives on the line, for their survival.[143]

Recognizing that the cold conditions combined with insufficient rest would hinder the time critical startup of the command module prior to reentry, at 133 hours into flight Mission Control gave Lovell the okay to fully power up the LM to raise the cabin temperature, which included restarting the LM's guidance computer. Having the LM's computer running enabled Lovell to perform a navigational sighting and calibrate the LM's Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU). With the lunar module's computer aware of its location and orientation, the command module's computer was later calibrated in a reverse of the normal procedures used to set up the LM, shaving steps from the restart process and increasing the accuracy of the PGNCS-controlled reentry.[145]

Reentry and splashdown

Despite the accuracy of the transearth injection, the spacecraft slowly drifted off course, necessitating a correction. As the LM's guidance system had been shut down following the PC+2 burn, the crew was told to use the line between night and day on the Earth to guide them, a technique used on NASA's Earth-orbit missions but never on the way back from the Moon.[143] This DPS burn, at 105:18:42 for 14 seconds, brought the projected entry flight path angle back within safe limits. Nevertheless, yet another burn was needed at 137:40:13, using the LM's reaction control system (RCS) thrusters, for 21.5 seconds. The SM was jettisoned less than half an hour later, allowing the crew to see the damage for the first time, and photograph it. They reported that an entire panel was missing from the SM's exterior, the fuel cells above the oxygen tank shelf were tilted, that the high-gain antenna was damaged, and there was a considerable amount of debris elsewhere.[146] Haise could see possible damage to the SM's engine bell, validating Kranz's decision not to use the SPS.[143] The crew then moved out of the LM back into the CM and reactivated its life support systems.[147]

The last problem to be solved was how to separate the lunar module a safe distance away from the command module just before reentry. The normal procedure, in lunar orbit, was to release the LM and then use the service module's RCS to pull the CSM away, but by this point, the SM had already been released. Grumman, manufacturer of the LM, assigned a team of University of Toronto engineers, led by senior scientist Bernard Etkin, to solve the problem of how much air pressure to use to push the modules apart. The astronauts applied the solution, which was successful.[148] The LM reentered Earth's atmosphere and was destroyed, the remaining pieces falling in the deep ocean.[119][149] Apollo 13's final midcourse correction had addressed the concerns of the Atomic Energy Commission, which wanted the cask containing the plutonium oxide intended for the SNAP-27 RTG to land in a safe place. The impact point was over the Tonga Trench in the Pacific, one of its deepest points, and the cask sank 10 kilometers (6 mi; 5 nmi) to the bottom. Later helicopter surveys found no radioactive leakage.[143]

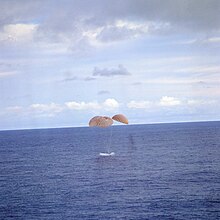

Ionization of the air around the command module during reentry would typically cause a four-minute communications blackout. Apollo 13's shallow reentry path lengthened this to six minutes, longer than had been expected; controllers feared that the CM's heat shield had failed.[150] Odyssey regained radio contact and splashed down safely in the South Pacific Ocean, 21°38′24″S 165°21′42″W / 21.64000°S 165.36167°W,[151] southeast of American Samoa and 6.5 km (4.0 mi; 3.5 nmi) from the recovery ship, USS Iwo Jima.[152] Although fatigued, the crew was in good condition except for Haise, who had developed a serious urinary tract infection because of insufficient water intake.[138] The crew stayed overnight on the ship and flew to Pago Pago, American Samoa, the next day. They flew to Hawaii, where President Richard Nixon awarded them the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor.[153] They stayed overnight, and then were flown back to Houston.[154]

En route to Honolulu, President Nixon stopped at Houston to award the Presidential Medal of Freedom to the Apollo 13 Mission Operations Team.[155] He originally planned to give the award to NASA administrator Thomas O. Paine, but Paine recommended the mission operations team.[156]

Public and media reaction

Nobody believes me, but during this six-day odyssey, we had no idea what an impression Apollo 13 made on the people of Earth. We never dreamed a billion people were following us on television and radio, and reading about us in banner headlines of every newspaper published. We still missed the point on board the carrier Iwo Jima, which picked us up, because the sailors had been as remote from the media as we were. Only when we reached Honolulu did we comprehend our impact: there we found President Nixon and [NASA Administrator] Dr. Paine to meet us, along with my wife Marilyn, Fred's wife Mary (who, being pregnant, also had a doctor along just in case), and bachelor Jack's parents, in lieu of his usual airline stewardesses.

— Jim Lovell[138]

Worldwide interest in the Apollo program was reawakened by the incident; television coverage was seen by millions. Four Soviet ships headed toward the landing area to assist if needed,[157] and other nations offered assistance should the craft have to splash down elsewhere.[158] President Nixon canceled appointments, phoned the astronauts' families, and drove to NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, where Apollo's tracking and communications were coordinated.[157]

The rescue received more public attention than any spaceflight to that point, other than the first Moon landing on Apollo 11. There were worldwide headlines, and people surrounded television sets to get the latest developments, offered by networks who interrupted their regular programming for bulletins. Pope Paul VI led a congregation of 10,000 people in praying for the astronauts' safe return; ten times that number offered prayers at a religious festival in India.[159] The United States Senate on April 14 passed a resolution urging businesses to pause at 9:00 pm local time that evening to allow for employee prayer.[157]

An estimated 40 million Americans watched Apollo 13's splashdown, carried live on all three networks, with another 30 million watching some portion of the 6½ hour telecast. Even more outside the U.S. watched. Jack Gould of The New York Times stated that Apollo 13, "which came so close to tragic disaster, in all probability united the world in mutual concern more fully than another successful landing on the Moon would have".[160]

Investigation and response

Review board

Immediately upon the crew's return, NASA Administrator Paine and Deputy Administrator George Low appointed a review board to investigate the accident. Chaired by NASA Langley Research Center Director Edgar M. Cortright and including Neil Armstrong and six others,[note 6] the board sent its final report to Paine on June 15.[162] It found that the failure began in the service module's number 2 oxygen tank.[163] Damaged Teflon insulation on the wires to the stirring fan inside Oxygen Tank 2 allowed the wires to short circuit and ignite this insulation. The resulting fire increased the pressure inside the tank until the tank dome failed, filling the fuel cell bay (SM Sector 4) with rapidly expanding gaseous oxygen and combustion products. The pressure rise was sufficient to pop the rivets holding the aluminum exterior panel covering Sector 4 and blow it out, exposing the sector to space and snuffing out the fire. The detached panel hit the nearby high-gain antenna, disabling the narrow-beam communication mode and interrupting communication with Earth for 1.8 seconds while the system automatically switched to the backup wide-beam mode.[164] The sectors of the SM were not airtight from each other, and had there been time for the entire SM to become as pressurized as Sector 4, the force on the CM's heat shield would have separated the two modules. The report questioned the use of Teflon and other materials shown to be flammable in supercritical oxygen, such as aluminum, within the tank.[165] The board found no evidence pointing to any other theory of the accident.[166]

Mechanical shock forced the oxygen valves closed on the number 1 and number 3 fuel cells, putting them out of commission.[167] The sudden failure of Oxygen Tank 2 compromised Oxygen Tank 1, causing its contents to leak out, possibly through a damaged line or valve, over the next 130 minutes, entirely depleting the SM's oxygen supply.[168][169] With both SM oxygen tanks emptying, and with other damage to the SM, the mission had to be aborted.[170] The board praised the response to the emergency: "The imperfection in Apollo 13 constituted a near disaster, averted only by outstanding performance on the part of the crew and the ground control team which supported them."[171]

Oxygen Tank 2 was manufactured by the Beech Aircraft Company of Boulder, Colorado, as subcontractor to North American Rockwell (NAR) of Downey, California, prime contractor for the CSM.[172] It contained two thermostatic switches, originally designed for the command module's 28-volt DC power, but which could fail if subjected to the 65 volts used during ground testing at KSC.[173] Under the original 1962 specifications, the switches would be rated for 28 volts, but revised specifications issued in 1965 called for 65 volts to allow for quicker tank pressurization at KSC. Nonetheless, the switches Beech used were not rated for 65 volts.[174]

At NAR's facility, Oxygen Tank 2 had been originally installed in an oxygen shelf placed in the Apollo 10 service module, SM-106, but which was removed to fix a potential electromagnetic interference problem and another shelf substituted. During removal, the shelf was accidentally dropped at least 5 centimeters (2 in), because a retaining bolt had not been removed. The probability of damage from this was low, but it is possible that the fill line assembly was loose and made worse by the fall. After some retesting (which did not include filling the tank with liquid oxygen), in November 1968 the shelf was re-installed in SM-109, intended for Apollo 13, which was shipped to KSC in June 1969.[175]

The Countdown Demonstration Test took place with SM-109 in its place near the top of the Saturn V and began on March 16, 1970. During the test, the cryogenic tanks were filled, but Oxygen Tank 2 could not be emptied through the normal drain line, and a report was written documenting the problem. After discussion among NASA and the contractors, attempts to empty the tank resumed on March 27. When it would not empty normally, the heaters in the tank were turned on to boil off the oxygen. The thermostatic switches were designed to prevent the heaters from raising the temperature higher than 27 °C (80 °F), but they failed under the 65-volt power supply applied. Temperatures on the heater tube within the tank may have reached 540 °C (1,000 °F), most likely damaging the Teflon insulation.[173] The temperature gauge was not designed to read higher than 29 °C (85 °F), so the technician monitoring the procedure detected nothing unusual. This heating had been approved by Lovell and Mattingly of the prime crew, as well as by NASA managers and engineers.[176][177] Replacement of the tank would have delayed the mission by at least a month.[137] The tank was filled with liquid oxygen again before launch; once electric power was connected, it was in a hazardous condition.[170] The board found that Swigert's activation of the Oxygen Tank 2 fan at the request of Mission Control caused an electric arc that set the tank on fire.[178]

The board conducted a test of an oxygen tank rigged with hot-wire ignitors that caused a rapid rise in temperature within the tank, after which it failed, producing telemetry similar to that seen with the Apollo 13 Oxygen Tank 2.[179] Tests with panels similar to the one that was seen to be missing on SM Sector 4 caused separation of the panel in the test apparatus.[180]

Changes in response

For Apollo 14 and subsequent missions, the oxygen tank was redesigned, the thermostats being upgraded to handle the proper voltage. The heaters were retained since they were necessary to maintain oxygen pressure. The stirring fans, with their unsealed motors, were removed, which meant the oxygen quantity gauge was no longer accurate. This required adding a third tank so that no tank would go below half full.[181] The third tank was placed in Bay 1 of the SM, on the side opposite the other two, and was given an isolation valve that could isolate it from the fuel cells and from the other two oxygen tanks in an emergency and allow it to feed the CM's environmental system only. The quantity probe was upgraded from aluminum to stainless steel.[182]

All electrical wiring in Bay 4 was sheathed in stainless steel. The fuel cell oxygen supply valves were redesigned to isolate the Teflon-coated wiring from the oxygen. The spacecraft and Mission Control monitoring systems were modified to give more immediate and visible warnings of anomalies.[181] An emergency supply of 19 litres (5 US gal) of water was stored in the CM, and an emergency battery, identical to those that powered the LM's descent stage, was placed in the SM. The LM was modified to make transfer of power from the LM to the CM easier.[183]

Aftermath

On February 5, 1971, Apollo 14's LM, Antares, landed on the Moon with astronauts Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell aboard, near Fra Mauro, the site Apollo 13 had been intended to explore.[184] Haise served as CAPCOM during the descent to the Moon,[185] and during the second EVA, during which Shepard and Mitchell explored near Cone crater.[186]

None of the Apollo 13 astronauts flew in space again. Lovell retired from NASA and the Navy in 1973, entering the private sector.[187] Swigert was to have flown on the 1975 Apollo–Soyuz Test Project (the first joint mission with the Soviet Union) but was removed as part of the fallout from the Apollo 15 postal covers incident. He took a leave of absence from NASA in 1973 and left the agency to enter politics, being elected to the House of Representatives in 1982, but died of cancer before he could be sworn in.[188] Haise was slated to have been the commander of the canceled Apollo 19 mission, and flew the Space Shuttle Approach and Landing Tests before retiring from NASA in 1979.[189]

Several experiments were completed during Apollo 13, even though the mission did not land on the Moon.[190] One involved the launch vehicle's S-IVB (the Saturn V's third stage), which on prior missions had been sent into solar orbit once detached. The seismometer left by Apollo 12 had detected frequent impacts of small objects onto the Moon, but larger impacts would yield more information about the Moon's crust, so it was decided that, beginning with Apollo 13, the S-IVB would be crashed into the Moon.[191] The impact occurred at 77:56:40 into the mission and produced enough energy that the gain on the seismometer, 117 kilometers (73 mi) from the impact, had to be reduced.[100] An experiment to measure the amount of atmospheric electrical phenomena during the ascent to orbit – added after Apollo 12 was struck by lightning – returned data indicating a heightened risk during marginal weather. A series of photographs of Earth, taken to test whether cloud height could be determined from synchronous satellites, achieved the desired results.[190]

As a joke, Grumman issued an invoice to North American Rockwell, prime contractor for the CSM, for "towing" the CSM most of the way to the Moon and back. Line items included 400001 miles at $1 each (plus $4 for the first mile); $536.05 for battery charging; oxygen; and four nights at $8 per night for an "additional guest in room" (Swigert). After a 20% "commercial discount", and a 2% discount for timely payment, the final total was $312,421.24. North American declined payment, noting that it had ferried three previous Grumman LMs to the Moon without compensation.[192][193][194]

The CM was disassembled for testing and parts remained in storage for years; some were used for a trainer for the Skylab Rescue Mission. That trainer was subsequently displayed at the Kentucky Science Center. Max Ary of the Cosmosphere made it a project to restore Odyssey; it is on display there, in Hutchinson, Kansas.[195]

Apollo 13 was called a "successful failure" by Lovell.[196] Mike Massimino, a Space Shuttle astronaut, stated that Apollo 13 "showed teamwork, camaraderie and what NASA was really made of".[120] The response to the accident has been repeatedly called "NASA's finest hour";[197][198][199][200] it is still viewed that way.[120] Author Colin Burgess wrote, "the life-or-death flight of Apollo 13 dramatically evinced the colossal risks inherent in manned spaceflight. Then, with the crew safely back on Earth, public apathy set in once again."[201]

William R. Compton, in his book about the Apollo Program, said of Apollo 13, "Only a heroic effort of real-time improvisation by mission operations teams saved the crew."[202] Rick Houston and Milt Heflin, in their history of Mission Control, stated, "Apollo 13 proved mission control could bring those space voyagers back home again when their lives were on the line."[203] Former NASA chief historian Roger D. Launius wrote, "More than any other incident in the history of spaceflight, recovery from this accident solidified the world's belief in NASA's capabilities".[204] Nevertheless, the accident convinced some officials, such as Manned Spaceflight Center director Gilruth, that if NASA kept sending astronauts on Apollo missions, some would inevitably be killed, and they called for as quick an end as possible to the program.[204] Nixon's advisers recommended canceling the remaining lunar missions, saying that a disaster in space would cost him political capital.[205] Budget cuts made such a decision easier, and during the pause after Apollo 13, two missions were canceled, meaning that the program ended with Apollo 17 in December 1972.[204][206]

Popular culture, media and 50th anniversary

The 1974 movie Houston, We've Got a Problem, while set around the Apollo 13 incident, is a fictional drama about the crises faced by ground personnel when the emergency disrupts their work schedules and places further stress on their lives. Lovell publicly complained about the movie, saying it was "fictitious and in poor taste".[207][208]

"Houston ... We've Got a Problem" was the title of an episode of the BBC documentary series A Life At Stake, broadcast in March 1978. This was an accurate, if simplified, reconstruction of the events.[209] In 1994, during the 25th anniversary of Apollo 11, PBS released a 90-minute documentary titled Apollo 13: To the Edge and Back.[210][211]

Following the flight, the crew planned to write a book, but they all left NASA without starting it. After Lovell retired in 1991, he was approached by journalist Jeffrey Kluger about writing a non-fiction account of the mission. Swigert died in 1982 and Haise was no longer interested in such a project. The resultant book, Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13, was published in 1994.[212]

The next year, in 1995, a film adaptation of the book, Apollo 13, was released, directed by Ron Howard and starring Tom Hanks as Lovell, Bill Paxton as Haise, Kevin Bacon as Swigert, Gary Sinise as Mattingly, Ed Harris as Kranz, and Kathleen Quinlan as Marilyn Lovell. James Lovell, Kranz, and other principals have stated that this film depicted the events of the mission with reasonable accuracy, given that some dramatic license was taken. For example, the film changes the tense of Lovell's famous follow-up to Swigert's original words from, "Houston, we've had a problem" to "Houston, we have a problem".[107][213] The film also invented the phrase "Failure is not an option", uttered by Harris as Kranz in the film; the phrase became so closely associated with Kranz that he used it for the title of his 2000 autobiography.[213] The film won two of the nine Academy Awards it was nominated for, Best Film Editing and Best Sound.[214][215]

In the 1998 miniseries From the Earth to the Moon, co-produced by Hanks and Howard, the mission is dramatized in the episode "We Interrupt This Program". Rather than showing the incident from the crew's perspective as in the Apollo 13 feature film, it is instead presented from an Earth-bound perspective of television reporters competing for coverage of the event.[216]

In 2020, the BBC World Service began airing 13 Minutes to the Moon, radio programs which draw on NASA audio from the mission, as well as archival and recent interviews with participants. Episodes began airing for Season 2 starting on March 8, 2020, with episode 1, "Time bomb: Apollo 13", explaining the launch and the explosion. Episode 2 details Mission Control's denial and disbelief of the accident, with other episodes covering other aspects of the mission. The seventh and final episode was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In "Delay to Episode 7", the BBC explained that the presenter of the series, medical doctor Kevin Fong, had been called into service.[217][218]

In advance of the 50th anniversary of the mission in 2020, an Apollo in Real Time site for the mission went online, allowing viewers to follow along as the mission unfolds, view photographs and video, and listen to audio of conversations between Houston and the astronauts as well as between mission controllers.[219] Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, NASA did not hold any in-person events during April 2020 for the flight's 50th anniversary, but premiered a new documentary, Apollo 13: Home Safe on April 10, 2020.[220] A number of events were rescheduled for later in 2020.[221]

Gallery

-

Lovell practices deploying the ALSEP during training

-

The Apollo 13 launch vehicle being rolled out, December 1969

-

The "mailbox" at Mission Control during the Apollo 13 mission

-

Lunar Module Aquarius after it was jettisoned above the Earth

-

Mission Control celebrates the successful splashdown

-

The crew on board the USS Iwo Jima following splashdown

-

The crew speaking with President Nixon shortly after their return

-

Replica of the lunar plaque with Swigert's name that was to cover the one attached to Aquarius with Mattingly's name

-

The crater created by the S-IVB's impact, as photographed by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, 2010

Notes

- ^ The event is described as an explosion in modern NASA histories and accounts by the crew.[7][8] However, the formal accident report avoids the use of the term.[9] NASA engineers at the time preferred "tank failure", both because it was more accurate and to avoid the negative connotations around the word "explosion".[10]

- ^ No Apollo astronaut flew without life insurance, but the policies were paid for by private third parties whose involvement was not publicized.[15]

- ^ The role of the backup crew was to train and be prepared to fly in the event something happened to the prime crew.[26] Backup crews, according to the rotation, were assigned as the prime crew three missions after their assignment as backups.[27]

- ^ Some sources list Kerwin[36] and others list Pogue as the third member[37][38][39]

- ^ The record was set because the Moon was nearly at its furthest from Earth during the mission. Apollo 13's unique free return trajectory caused it to go approximately 100 kilometers (60 mi) further from the lunar far side than other Apollo lunar missions, but this was a minor contribution to the record.[124] A reconstruction of the trajectory by astrodynamicist Daniel Adamo in 2009 records the furthest distance as 400,046 kilometers (248,577 mi) at 7:34 pm EST (00:34:13 UTC). Apollo 10 holds the record for second-furthest at a distance of 399,806 kilometers (248,428 mi).[125]

- ^ The others were Robert F. Allnutt (Assistant to the Administrator, NASA Hqs.); John F. Clark (Director, Goddard Space Flight Center); Brig. General Walter R. Hedrick Jr. (Director of Space, DCS/RED, Hqs., USAF); Vincent L. Johnson (Deputy Associate Administrator-Engineering, Office of Space Science and Applications); Milton Klein (Manager, AEC-NASA Space Nuclear Propulsion Office); Hans M. Mark (Director, Ames Research Center).[161]

References

- ^ "Apollo 13 CM". N2YO.com. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ Orloff 2000, p. 309.

- ^ "Apollo 13 Command and Service Module (CSM)". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ "Apollo 13 Lunar Module / EASEP". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ Orloff 2000, p. 307.

- ^ "Apollo 13". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ Williams, David. "The Apollo 13 accident". NASA.

The Apollo 13 malfunction was caused by an explosion and rupture of oxygen tank no. 2 in the service module.

- ^ Cortright 1975, pp. 248–249: "I did, of course, occasionally think of the possibility that the spacecraft explosion might maroon us... Thirteen minutes after the explosion, I happened to look out of the left-hand window, and saw the final evidence pointing toward potential catastrophe. "

- ^ Accident report, p. 143.

- ^ Cooper 2013, p. 21: "Later, in describing what happened, NASA engineers avoided using the word "explosion;" they preferred the more delicate and less dramatic term "tank failure," and in a sense it was the more accurate expression, inasmuch as the tank did not explode in the way a bomb does but broke open under pressure."

- ^ a b "Apollo 11 Mission Overview". NASA. December 21, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Hacker & Grimwood 2010, p. 382.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, p. 285.

- ^ a b Weinberger, Howard C. "Apollo Insurance Covers". Space Flown Artifacts (Chris Spain). Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Neufeld, Michael J. (July 24, 2019). "Remembering Chris Kraft: Pioneer of Mission Control". Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Cass, Stephen (April 1, 2005). "Apollo 13, we have a solution". IEEE. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ Williams, Mike (September 13, 2012). "A legendary tale, well-told". Rice University Office of Public Affairs. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ Apollo Program Summary Report 1975, p. B-2.

- ^ Launius 2019, p. 186.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth; Hickok, Kimberly (March 31, 2020). "Apollo 13: The moon-mission that dodged disaster". Space.com. Future US. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: John L. Swigert". NASA. January 1983. Archived from the original on July 31, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, pp. 589–593.

- ^ "50 years ago: NASA names Apollo 11 crew". NASA. January 30, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 137.

- ^ a b Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 236.

- ^ "Apollo 13 Crew". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ "Charles M. Duke, Jr. Oral History". NASA. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ NASA 1970, p. 6.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (April 12, 2010). "13 things that saved Apollo 13, Part 3: Charlie Duke's measles". Universe Today. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 184.

- ^ Hersch, Matthew (July 19, 2009). "The fourth crewmember". Air & Space/Smithsonian. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood, & Swenson 1979, p. 261.

- ^ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 251.

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood, & Swenson 1979, p. 378.

- ^ Orloff 2000, p. 137.

- ^ "Oral History Transcript" (PDF) (Interview). Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. Interviewed by Kevin M. Rusnak. Houston, Texas: NASA. July 17, 2000. pp. 12-25–12-26. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 1, 2019.

- ^ "MSC 69–56" (PDF) (Press release). Houston, Texas: NASA. August 6, 1969. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ a b Mission Operations Report 1970, p. I-1.

- ^ Kranz 2000, p. 307.

- ^ Lovell & Kluger 2000, p. 79.

- ^ Morgan 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 362.

- ^ Lovell & Kluger 2000, p. 81.

- ^ Orloff 2000, p. 283.

- ^ Crafton, Jean (April 12, 1970). "Astros Wear Badge of Apollo". Daily News. New York City. p. 105 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Moran, Dan (October 2, 2015). "Apollo 13 astronaut Jim Lovell shares stories about Tom Hanks, Ron Howard". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ Moran, Dan (October 2, 2015). "Namesake Brings Personal Touch to Lovell Center Fete". Chicago Tribune. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Chaikin 1995, p. 291.

- ^ a b c Lovell & Kluger 2000, p. 87.

- ^ Lattimer 1988, p. 77.

- ^ "Medal, Robbins, Commemorative, Apollo 13 | National Air and Space Museum". airandspace.si.edu. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 74.

- ^ Orloff 2000, p. 284.

- ^ a b "Day 1: Earth orbit and translunar injection". Apollo Lunar Flight Journal. February 17, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "Apollo 10: Day 1, part 1: Countdown, launch and climb to orbit". Apollo Lunar Flight Journal. February 6, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 364.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, pp. 78, 81.

- ^ "MSC 70–9" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. January 8, 1970. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ "Apollo's Schedule Shifted by NASA". The New York Times. January 9, 1970. p. 17.

- ^ "Apollo 13 and 14 may be set back". The New York Times. UPI. January 6, 1970. p. 26.

- ^ a b Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 104.

- ^ Phinney 2015, p. 100.

- ^ Phinney 2015, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Phinney 2015, pp. 107–111.

- ^ Phinney 2015, p. 134.

- ^ Phinney 2015, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Harland 1999, p. 53.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 363.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 105.

- ^ Jones, Eric M. (April 29, 2006). "Lunar Landing Training Vehicle NASA 952". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ Harland 1999, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Harland 1999, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 29.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 42.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Science News 1970-04-04, p. 354.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 49.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 51.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 62.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 65.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, pp. 33, 65.

- ^ Apollo 13 Press Kit 1970, p. 73.

- ^ Jones, Eric M. (February 20, 2006). "Commander's stripes". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Turnill 2003, p. 316.

- ^ Jones, Eric M. (March 3, 2010). "Water Gun, Helmet Feedport, In-Suit Drink Bag, and Food Stick". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Accident report, p. 3-26.

- ^ a b Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 385.

- ^ a b Saturn 5 Launch Vehicle Flight Evaluation Report: AS-508 Apollo 13 Mission. George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama: NASA. June 20, 1970. MPR-SAT-FE-70-2. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Benson & Faherty 1979, pp. 494–499.

- ^ a b c Larsen 2008, p. 5-13.

- ^ Fenwick, Jim (Spring 1992). "Pogo". Threshold. Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ^ Larsen 2008, pp. 5-7–5-12.

- ^ Dotson, Kirk (Winter 2003–2004). "Mitigating Pogo on Liquid-Fueled Rockets" (PDF). Crosslink. 5 (1). El Segundo, California: The Aerospace Corporation: 26–29. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ^ Woods, W. David; Turhanov, Alexandr; Waugh, Lennox J., eds. (2016). "Launch and Reaching Earth Orbit". Apollo 13 Flight Journal. NASA. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (April 14, 2010). "13 things that saved Apollo 13, Part 5: Unexplained shutdown of the Saturn V center engine". Universe Today. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ Woods, W. David; Kemppanen, Johannes; Turhanov, Alexander; Waugh, Lennox J. (February 17, 2017). "Day 1: Transposition, Docking and Extraction". Apollo Lunar Flight Journal. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 367.

- ^ "Day 2: Midcourse correction 2 on TV". Apollo Lunar Flight Journal. February 17, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ Robin Wheeler (2009). "Apollo lunar landing launch window: The controlling factors and constraints". Apollo Lunar Flight Journal. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ NASA 1970, p. 8.

- ^ Woods, W. David; Turhanov, Alexandr; Waugh, Lennox J., eds. (2016). "Day 3: Before the storm". Apollo 13 Flight Journal. NASA. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ Houston, Heflin & Aaron 2015, p. 206.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, pp. 285–287.

- ^ a b c d e f g Woods, W. David; Kemppanen, Johannes; Turhanov, Alexander; Waugh, Lennox J. (May 30, 2017). "Day 3: 'Houston, we've had a problem'". Apollo Lunar Flight Journal. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Chaikin 1995, p. 292.

- ^ a b Houston, Heflin & Aaron 2015, p. 207.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 368.

- ^ Orloff 2000, pp. 152–157.

- ^ Accident report, p. 4-44.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, p. 293.

- ^ a b Chaikin 1995, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Houston, Heflin & Aaron 2015, p. 215.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, p. 299.

- ^ a b c d Cass, Stephen (April 1, 2005). "Houston, we have a solution, part 2". IEEE. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ Lovell & Kluger 2000, pp. 83–87.

- ^ a b "Apollo 13 Lunar Module/ALSEP". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

- ^ a b c Dunn, Marcia (April 9, 2020). "'Houston, we've had a problem': Remembering Apollo 13 at 50". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 369.

- ^ Glenday 2010, p. 13.

- ^ Adamo 2009, p. 37.

- ^ Adamo 2009, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d "Day 4: Leaving the Moon". Apollo Lunar Flight Journal. February 17, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ Cooper 2013, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Houston, Heflin & Aaron 2015, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 391.

- ^ Houston, Heflin & Aaron 2015, p. 224.

- ^ Pothier, Richard (April 16, 1970). "Astronauts Beat Air Crisis By Do-It-Yourself Gadget". Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. p. 12–C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Barell 2016, p. 154.

- ^ Smith, Yvette (September 24, 2015). "Putting a Square Peg in a Round Hole". NASA. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Cortright 1975, pp. 257–262.

- ^ Mission Operations Report 1970, pp. III‑17, III-33, III-40.

- ^ Cortright 1975, pp. 254–257.

- ^ a b Jones, Eric M. (January 4, 2006). "The frustrations of Fra Mauro: Part I". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c Cortright 1975, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Kennedy, A.R. (2014). "Biological effects of space radiation and development of effective countermeasures". Life Sciences in Space Research. 1 (1): 10–43. Bibcode:2014LSSR....1...10K. doi:10.1016/j.lssr.2014.02.004. PMC 4170231. PMID 25258703.

- ^ Mars, Kelli (April 16, 2020). "50 Years Ago: Apollo 13 Crew Returns Safely to Earth". NASA. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Cortright 1975, pp. 257–263.

- ^ Siceloff, Steven (September 20, 2007). "Generation Constellation Learns about Apollo 13". Constellation Program. NASA. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Cass, Stephen (April 1, 2005). "Houston, we have a solution, part 3". IEEE. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ Leopold, George (March 17, 2009). "Power engineer: Video interview with Apollo astronaut Ken Mattingly". EE Times. UMB Tech. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ "Apollo Flight Journal: Day 6 Part 4". NASA. Archived from the original on January 18, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, pp. 370–371.

- ^ "Apollo 13 Lunar Module / EASEP". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ "Bernard Etkin helped avert Apollo 13 tragedy". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ "Impact Sites of Apollo LM Ascent and SIVB Stages". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ Pappalardo, Joe (May 1, 2007). "Did Ron Howard exaggerate the reentry scene in the movie Apollo 13?". Air & Space/Smithsonian. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ Apollo 13 Mission Report 1970, p. 1-2.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 371.

- ^ "Heroes of Apollo 13 Welcomed by President and Loved Ones". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. April 19, 1970. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Apollo 13 Mission Report 1970, p. 10-5.

- ^ "Behind the Scenes of Apollo 13". Richard Nixon Foundation. April 11, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ "Remarks on Presenting the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Apollo 13 Mission Operations Team in Houston". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c NASA 1970, p. 15.

- ^ Benson & Faherty 1979, pp. 489–494.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, p. 316.

- ^ Gould, Jack (April 18, 1970). "TV: Millions of viewers end vigil for Apollo 13". The New York Times. p. 59.

- ^ Accident report, pp. 1-1–1-4.

- ^ Accident report, p. 15.

- ^ Accident report, p. 4-36.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, pp. 372–373.

- ^ Accident report, pp. 5-6–5-7, 5-12–5-13.

- ^ Accident report, p. 4-37.

- ^ Accident report, p. 4-40.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 372.

- ^ Accident report, p. 4-43.

- ^ a b Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 375.

- ^ Accident report, p. ii.

- ^ Accident report, p. 4-2.

- ^ a b Accident report, p. 4-23.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, p. 374.

- ^ Accident report, pp. 4–19, 4–21.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Williams, David R. "The Apollo 13 Accident". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, p. 333.

- ^ Accident report, appendix F–H, pp. F-48–F-49.

- ^ Accident report, appendix F–H, pp. F-70–F-82.

- ^ a b Gatland 1976, p. 281.

- ^ Apollo 14 Press Kit 1971, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Apollo 14 Press Kit 1971, pp. 96–98.

- ^ "Apollo 14 mission". USRA. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Eric M., ed. (January 12, 2016). "Landing at Far Mauro". Apollo 14 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Eric M., ed. (September 29, 2017). "Climbing Cone Ridge – where are we?". Apollo 14 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: James A. Lovell". NASA. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ Carney, Emily (August 29, 2014). "For Jack Swigert, on his 83rd birthday". AmericaSpace. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth; Hickok, Kimberly (April 10, 2020). "Astronaut Fred Haise: Apollo 13 Crewmember". Space.com. Future US. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "Apollo 13 mission: Science experiments". USRA. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ Harland 1999, p. 50.

- ^ "The Apollo 13 Invoice..." Spaceflight Insider. December 8, 2013. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Tongue-in-Cheek-Bill Asks Space Tow Fee". Spokane Daily Chronicle. April 18, 1970. p. 7. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "'Towing' Fee Is Asked by Grumman". The New York Times. April 18, 1970. p. 13. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Apollo 13 Capsule Headed for Kansas". The Manhattan Mercury. Manhattan, Kansas. Associated Press. December 29, 1996. p. A2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cortright 1975, pp. 247–249.

- ^ Shiflett, Kim (April 17, 2015). "Members of Apollo 13 Team Reflect on 'NASA's Finest Hour'". NASA. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ Foerman, Paul; Thompson, Lacy, eds. (April 2010). "Apollo 13 – NASA's 'successful failure'" (PDF). Lagniappe. 5 (4). Hancock County, Mississippi: John C. Stennis Space Center: 5–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2013.